Recently, Italy’s financial crime corps published the result of an investigation that drove them to charge six managers from an Italian drone-making company. Alpi Aviation, they contended, had been taken over by two major Chinese governmental companies with “opaque methods” meant to obscure the final owner.

The news rippled through Italy at a time of heightened attention towards securing the country’s strategic entities. The affair is now under the lens of the Prime Minister’s office, pending verification, with administrative procedures to follow (more in our report). And it was also noticed by one Ryan Fedasiuk, Research Analyst at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), who noted that the event was hardly surprising and pointed at a report he had co-authored on the matter.

The (alleged) Alpi Aviation affair does indeed fit in like a puzzle piece. The CSET report details the role of Chinese “science and technology diplomats”, scouters who pose as private entities and “act as brokers as part of China’s broader strategy to acquire foreign technology” by identifying and facilitating the acquisition of know-how by investing in technically-advanced companies, all while enjoying the backing of Beijing.

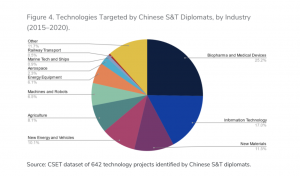

The work goes on to illustrate what the researchers found after delving into 642 of the thousands of reports “filed by the S&T directorates of Chinese embassies and consulates” across 52 countries. Said scouters seem set on finding companies with strategic value and potential impact on State security, from biopharma to information technology, as well as new materials, energy, vehicles, agriculture, robotics, aerospace, marine tech, et cetera.

As detailed by the researchers, Beijing tends to exploit the ambiguity that pervades the demarcation between public and private in China, where a company could be compelled by law to share its information with the authorities if required to – one of the key arguments behind the US’ rejection of Chinese 5G equipment.

China’s S&T emissaries also wander into the grey area of dual-use technologies (i.e. equipment that could theoretically be employed for both civilian and military activities). These methods were documented in another report from 2019, authored by C4ADS, detailing Beijing’s “IDAR” strategy with regards to this technology: introduce, digest, absorb, re-innovate.

The latter work also focusses on the so-called “Military-Civil Fusion” strategy, promoted at the national level by none other than Xi Jinping in 2015 and enhanced under a specially-designed Committee chaired by the Chinese president himself. According to the US Department of State, it’s an “aggressive, national strategy” to “enable [China] to develop the most technologically advanced military in the world.”

Capital distribution, write the authors, is a key element of that committee’s drive to “stimulate civilian-military collaboration” – to the tune of nearly $57 billion in 2018 only – and “blur the lines between industrial and defense supply chains.”

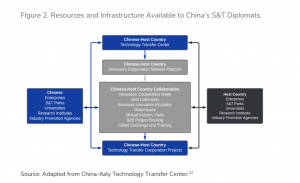

Enter Italy, where Alpi Aviation is more than a blip on the radar. In fact, an entire institution – the China-Italy Technology Transfer Center – has been established over the years for Beijing’s emissaries to piggyback onto vis a vis the identification of potentially interesting companies.

That Center partners with Italy’s Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR), as well as the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, and has active branches and partnerships with the University of Bergamo in Northern Italy and Naples’ City of Science in the South.

According to the official website, the project is meant to promote “the internationalization activities of the research-business systems of the Italy-China axis, [as well as] economic synergies and collaborations in the field of scientific and technological research.” Further details are scarce, and social media pages have been dormant for a couple years.

That Center is just the Italian local chapter of the wider Chinese International Technology Transfer Center (CITTC), a globally-scaled version of the same operation with dozens of partnering countries, the structure of which was laid out by CSET researchers.

A CITTC infographic details some Italian companies that work with the institutions in Bergamo and Naples. Such as Sesto Sensor, a company producing fibre-optic sensors for power lines, oil and gas ducts, or Elias, which specialises in environmental management systems and electric/electronic planning.

Chances are, companies such as these could end up becoming the new Alpi Aviation. It’s unmistakable, CSET says: Beijing’s operations are ultimately geared at enhancing its own technological and military might, in line with the Chinese Communist Party’s goals as laid out in President Xi’s reforms: Made in China 2025, Medium and Long Term Plan for Science and Technology Development (2006-2020) and Strategic Emerging Industries Strategy.