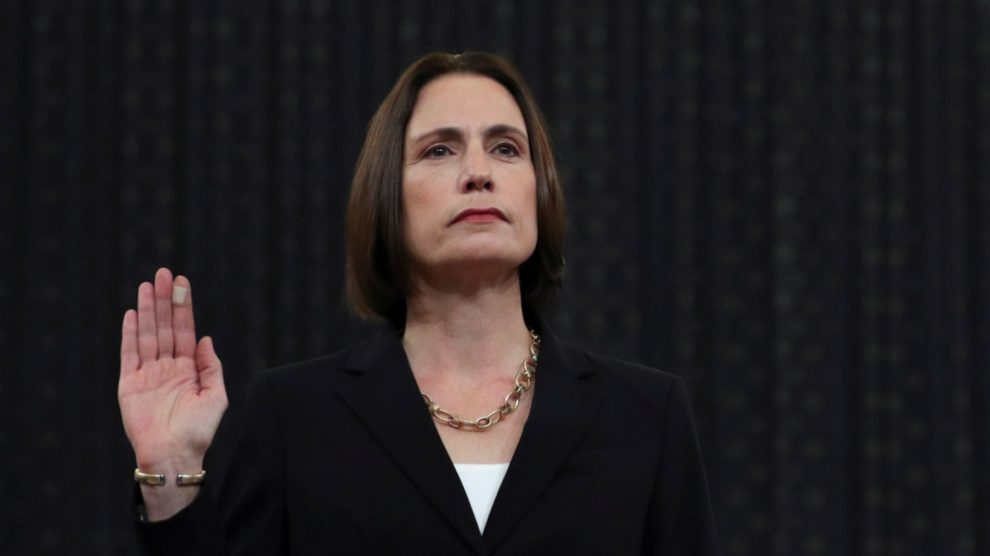

“Populist parties in Italy making common cause with parties that they think are similar in Russia is a big mistake.” Thus spoke Fiona Hill, one of the world’s leading experts on Russia, a life devoted to American intelligence and then in the White House – first under George Bush and Barack Obama, then as head of the European and Eurasian Affairs at the National Security Council under Donald Trump.

The expert was speaking at a webinar hosted by Formiche, where she presented her latest autobiographical book There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century (Mariner Books). Speaking alongside the director of Aspenia and former Deputy Foreign Minister Marta Dassù, Ms Hill warned that one cannot be naïve with Russian President Vladimir Putin and that Italy is still a target of Russian intelligence and the Russian government.”

There is no shortage of evidence: last March, one month after Prime Minister Mario Draghi took office, Navy officer Walter Biot was arrested in Rome was caught red-handed in selling NATO secrets to two Russian intelligence agents. Nor is it a mystery that the Italian capital is crisscrossed by undercover Kremlin men, ranging from spies to the many oligarchs who have business and interests in Italy, as detailed in the new book by Italian journalists Jacopo Iacoboni and Gianluca Paolucci, Oligarchi (Edizioni Laterza).

Diplomacy, Ms Hill explained, is another matter altogether. “I think it’s absolutely fine, and also advisable, for Italy to try to play a role like that. Italy does have a different history of connections with Russia and the Soviet Union than many other European countries do – there have long been ties between Italy and the Russian Empire.”

Problems arise when mediation becomes political collusion, and as Ms Hill noted, some Italian parties lack awareness of the ways Russia tries to manipulate other countries. “The Russians use money as means of influence, not just hacking and ransomware attacks and stealing secrets.” Russian politicians do not travel to Italy on official State business, continued the expert, but rather attend conventions and “dialogues of civilization or meeting of like-minded populist parties.”

Underestimating these endeavours is a huge mistake, as these tactics replicate Josif Stalin’s own: “he would invite in communists and fellow socialists from around the world, but the whole purpose was to influence them on their behalf, only to use them as assets later. This isn’t a two-way street, it’s a one-way street.”

Ms Hill spoke from experience. In the book (read the excerpt) she recounts having seen Mr Putin several times while attending meetings of international experts on Russia convened in the Kremlin’s shadow, with the ostensible purpose of discussing international politics. The Valdai Club meetings, she explained, “were part of an overt Kremlin effort to influence the opinions of Western academics and commentators about [Mr] Putin’s Russia.”

The same risk exists today with parties forming official relations with the Russian government. It happened with Matteo Salvini’s League, which signed an agreement with Mr Putin’s party, United Russia, in 2017; this was later renewed by the youth sections of both parties and is still in force today.

Ms Hill maintained that Russian intervention in our political systems has become more evident over the years. Countries like Italy, France or Germany are no less vulnerable to manipulation than Ukraine or other former Soviet republics, and even intelligence operations, she says, have become more shameless.

“Let me offer an example […] with the [2018] poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salsbury, in the UK. This was a spy on spy act” where Russian operatives filled a bottle of perfume with the banned nerve agent Novichok, enough to kill 4,000 people. After soaking the Skripal’s doorknob they discarded the bottle in a donation receptacle of a charity store, resulting in one death, several injuries and widespread contamination.

Political figures around the world downplayed the gravity of the incident at the time, she recalled, thinking that it would not happen elsewhere. That’s also a mistake, according to Ms Hill; “I hate to say it, [but] imagine if this was Pisa,” she quipped, adding that a drastic and necessary solution would be to “immediately expel all intelligence operatives” caught stealing secrets in Italy and in other European countries.

Underestimating Russian penetration into the political system is a risk that the United States still faces today. The White House is no longer inhabited by Mr Trump, against whom Hill testified in a now-famous hearing in his first impeachment trial for the “Ukrainegate” case, and yet the threat remains. “Our democracy is letting its guard down,” warned the expert.

President Biden has made the country more resilient, she continued, but he’s in trouble on the domestic front and “not all parties understand the risk that American democracy ran on January 6th. So much so that the hypothesis of a Trump candidacy in 2024 is still alive. The former president “does not have the majority of the country, but he has a very strong minority among the Republicans. Many in the party can’t stand him, but are willing to re-elect him to displease the Democrats.”