On May 21 the G7 environment ministers confirmed their commitment to implement the 2015 Paris Agreement, without specifying in detail how to do that except by indicating 2025 as the deadline for the elimination of subsidies to fossil fuels.

The document also states that the G7 alone will not be able to meet the challenge of climate change, and it vaguely references the expectations and the need to collaborate with other economies with increasing emissions, starting with China and India, and with the large non-G7/OECD economies with higher per capita emissions, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia as well as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. As a sidenote, Canada’s, Australia’s and the US’ emissions per capita are at least double those of the European Union.

The document certainly marks a step forward compared to the Trump era because it is shared by the US. However, the 16 pages and 46 points dedicated to climate could have offered some updated assessment of the reasons that have prevented the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Starting with the commitments underwritten by the individual countries, which are deemed largely insufficient by the United Nations Report of 26 February 2021 NDC Syntesis Report.

That report highlights that, based on available data, a mere 0.7% reduction in emissions (compared to 2010) is expected by 2030. For perspective, net emissions should be reduced by 45% to achieve the goal of limiting the temperature increase of 1.5°C. G7 ministers recognize the need to review the “architecture” of the Paris agreement, but offer no guidance.

It would also have been useful to see more precise indications on the measures that the Seven suggest to adopt by 2030 to push the global economy towards decarbonisation. According to the International Energy Agency report from May 2021, “Net Zero by 2050. A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector,” projects for the exploration of new oil fields and gas should be phased out starting from 2021, along with the creation of new coal mines and mine extensions. Which means that the use of oil, gas and coal must be considered progressively marginal in all sectors of the economy. And in this regard, it would have been useful to have an assessment of the program for the decarbonization of the Chinese economy, which will have significant effects on the future of global emissions.

Following the meeting of the G7 Environment Ministers in the past week, the Agency has published three reports. They are far from comforting.

“Oil Market Report June 2021” estimates that the demand for petroleum products is destined to reach pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022, driven not only by transport but also by a strong growth in demand for plastic. Meanwhile, oil extraction will continue to grow both in Saudi Arabia and in OPEC+ countries, as well as in the US, Canada, Brazil and Norway.

“Gas market Report Q2 2021” estimates that in 2021 alone the demand for gas is destined to grow by more than 3%, supported in particular by the growth in consumption in China, India and in the emerging economies of Asia.

“Financing clean energy transitions in emerging and developing economies,” prepared in collaboration with the World Bank and the World Economic Forum, indicates that without a transition to clean energy, the developing countries and emerging economies of Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Asia (without China but with India and Indonesia) will contribute to CO2 emissions growth by at least 5 billion tons within the next 20 years. At least one billion dollars in investments is needed by 2030 to facilitate the energy transition of these economies, to be supported by economic and technological cooperation promoted by large economies (including China).

Evidently this data indicates a different trend from the one envisioned by the “Net Zero by 2050” objective, and gives the measure of the challenge. Still, the G7 leaders meeting provides some important indications.

Their commitment to slash the cumulative emissions of their countries by 50% within 2030, associated with the promotion of the green economy, constitutes a common working basis between Europe, the US, Canada and Japan for the convergence towards a G7 Green Deal able to show the way to the entire global economy, starting with the transport sector, indicated as a priority for the elimination of internal combustion cars.

The commitment to support the energy transition of the less developed and emerging economies with a loan of $ 100 billion a year confirms an agreement that was already made in 2009 and never respected until today. This is a qualitative leap that meets the forecasts of the IEA, World Bank and World Economic Forum report.

But, as the environment ministers recalled, the G7 cannot do everything alone.

It is clear that the challenge of decarbonization requires the collaboration of China, India, Russia and Saudi Arabia. And it is equally evident, as demonstrated by the 25 COPs that have taken place since 1995, that COP26 will be successful if all the great economies of the planet are aligned in the same perspective and with converging policies.

In this regard, it is interesting to note that many of the indications and commitments of the G7 are convergent with the programs already launched by China, as well as with many programs being defined by India and Saudi Arabia.

For example, the long-distance and high-capacity electricity interconnection (Global Energy Interconnection) between renewable energy production centers, which are often remote, and the consumption areas is a response to the demand for growth in electricity consumption without increasing the use of oil, gas and coal. The initiative, launched by China, boasts important European technology partners, including ABB and Siemens.

In this context, the project recently launched by Xlinks (an English company) for the production of 10.5 gigawatts of renewable energy in the Saharan Morocco, to be transferred to the United Kingdom with a high-capacity, 3,800 kilometers long submarine cable, is interesting. Riyadh’s ACWA Power Renewable Energy Holding and the Chinese Silk Road Fund are partners of Xlinks.

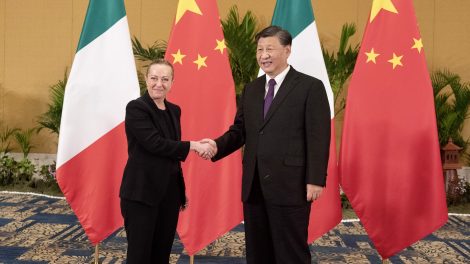

In short, it is desirable that the G7 be the starting point for a broader convergence, one which may facilitate dialogue and information sharing between the initiatives launched by the large economies to build concrete foundations for cooperation towards decarbonisation. The G20 chaired by Italy may well be the right occasion.