Italy is out of the BRI. Three days ago, Rome delivered to Beijing a note to announce its withdrawal from the Belt and Road Initiative, the massive infrastructure and investment project launched ten years ago by President Xi Jinping, which Italy had joined in 2019. This was revealed by Corriere della Sera, which points out that the move was made “without any public communication, as agreed with the Chinese authorities.”

- It’s about the convenience of both parties: Rome intends to avoid repercussions (such as economic backlash), while Beijing wants to limit the bad publicity arising from the former leaving the project – which is already suffering from financial problems.

A matter of method. Rome’s withdrawal came in the form of an explicit cancellation of the agreement, according to Corriere della Sera. Italy had tried to change the terms of the agreement itself, aiming to trigger the cancellation for lack of an explicit renewal, but China refused after several weeks of diplomatic ping-pong. Therefore, on Sunday – three weeks before the deadline that would have triggered the automatic five-year extension – the note was delivered.

Who laid the groundwork. Ambassador Riccardo Guariglia, The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Secretary General, had travelled to China during the summer to discuss the withdrawal. Then came Foreign Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Antonio Tajani.

- These meetings reaffirmed Rome and Beijing’s commitment to their strategic partnership (launched in 2004 during the premiership of Silvio Berlusconi).

- That’s meant to offset Italy’s exit from the BRI, according to the officials.

- They also prepared the ground for the visit of Italian President Sergio Mattarella to mark the 700th anniversary of the death of Marco Polo in early 2024.

Ongoing contact (but a revised partnership). FM Tajani said on Wednesday that an intergovernmental meeting between Italy and China had already been convened for next year in Verona to discuss all international trade issues. “There are still very good relations and ties, even if the country is also one of our competitors at the global level,” he remarked, explaining that the BRI “has not had the hoped-for effects, quite the opposite” and that “non-participation” is not “a negative action towards China.”

How did this happen? Italy joined the BRI in 2019 under then-PM Giuseppe Conte, the first and only G-7 country to do so, causing great consternation among its allies, especially the United States. The MoU’s renewal would have further embarrassed Rome as it’s readying to take up the G-/ presidentship in 2024.

- As Mr Conte himself (who’s now head of the Five Star Movement) recently explained, the agreement was “intended to rebalance our trade and was also demanded by the business community. Then, of course, came the pandemic and, when assessing the impact of this agreement, you have to take into account that China and Italy were the countries most affected.”

The reality check. However, Chinese exports to Italy have increased significantly since 2019. The opposite did not happen, pushing the trade deficit in Beijing’s favour – from €383.7 billion in 2019 to €844.4 billion in 2022, more than double in three years.

- Italy’s import-export trends with China “have not been significantly influenced by the Silk Road, but rather by cyclical and structural phenomena in the global economy,” economist Lorenzo Codogno told our sister website, noting that that’s why rebalancing trade “will not be easy at all.”

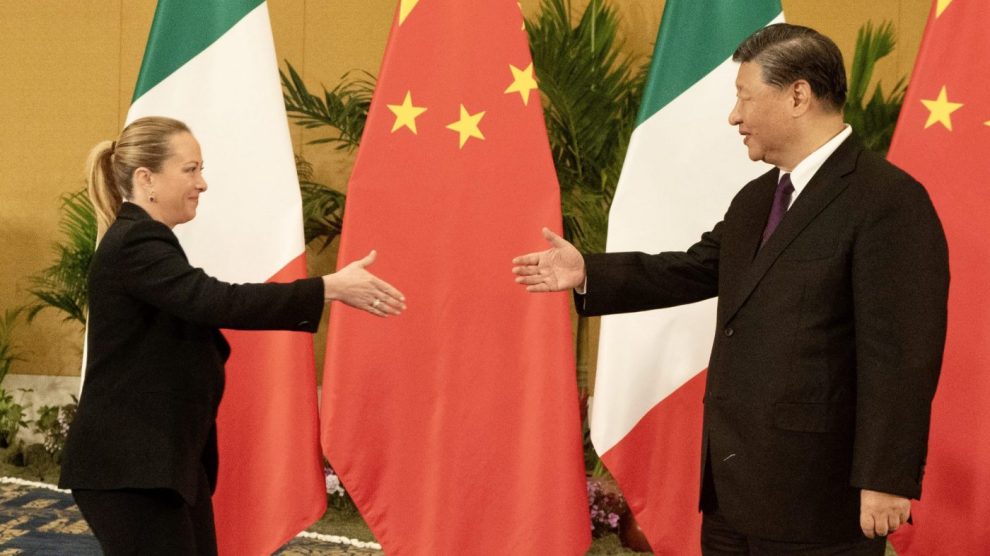

The writing was on the wall. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni can now claim she has kept a key foreign policy promise, the second after announcing Rome’s support to Kyiv in the face of Russian aggression. Before the elections in September 2022, she even told Taiwanese news agency CNA (not a trivial choice) that entering the BRI had been a “big mistake,” noting that “if [she had had] to sign the renewal of that memorandum tomorrow morning, I would hardly see the political conditions.”

Back on track. Interviewed by our sister website, Senator Giulio Terzi – Chairman of the European Union Policies Committee and head of diplomatic relations of PM Meloni’s party, Brothers of Italy – recalled that the EU in 2019 had revised its description of China into “a negotiating partner, with which the EU must find a balance of interests; an economic competitor, that aspires to technological leadership; and a systemic rival, that promotes alternative governance models.”

- Italy’s frame of reference must be European, he stressed, noting that Europe and the Atlantic countries “are clear on certain areas” like emerging technologies, supply chains in strategic sectors, cybersecurity and reciprocity, as well as human rights and international law.

- Thus, he concluded, PM Meloni’s government has “demonstrated a line of coherence and linearity” on foreign policy – most notably, in one of the most important dossiers of foreign policy and global multilateral policy.”