US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is back in Europe this week, visiting France as part of an ongoing effort to smooth tensions after the Biden administration angered it by announcing a submarine deal with Australia also involving Great Britain that scuttled a separate deal France had with Australia, a deal known as AUKUS.

Mr Blinken, who will be accompanied by US climate envoy John Kerry and US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, will chair the ministerial meeting of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, but the focus of the visit will be on resetting bilateral ties with France, which withdrew its ambassador after the submarine deal was announced last month.

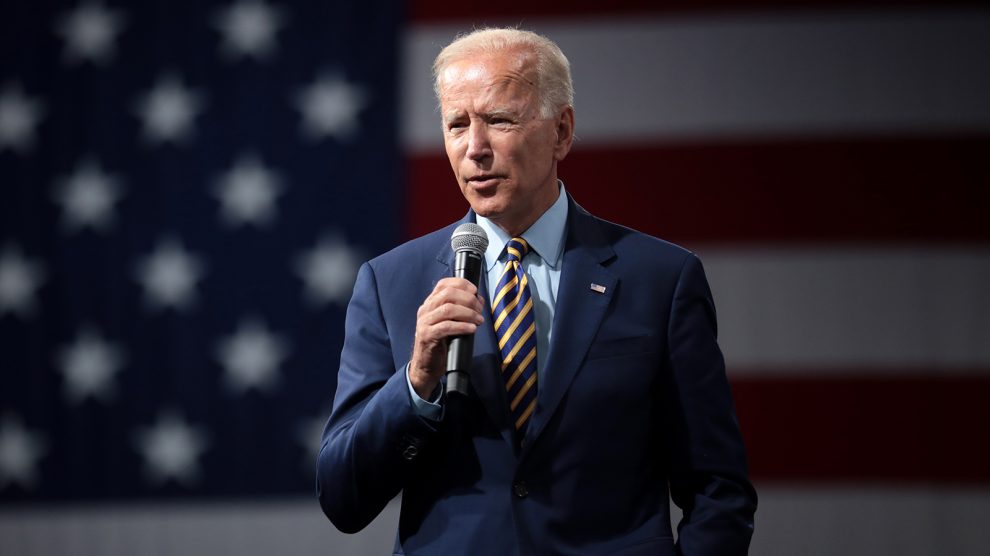

While all eyes will be on the US-France relationship this week, the past two months have raised broader concerns about President Biden’s foreign policy approach and how serious his team is about closely coordinated with its European partners. After spending its early months presenting itself as a return to strategic reliability and normalcy and a strong showing on Biden’s first overseas trip as president to Europe in June, the rest of the summer and early fall was a shaky period for Biden’s national security team. In addition to the ruckus over AUKUS, the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan and America’s lack of close coordination raised concerns among its closest allies in the Transatlantic relationship.

The brief honeymoon period in the Transatlantic relationship came to a close this early summer, and now Europe and the US are settling into a new phase of their relationship under this new U.S. administration. One important signifier of an attempt at a deeper Transatlantic relationship came this week in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where American and European officials met and announced new initiatives to deepen cooperation on technology and trade, all with an eye to the bigger competition with China and its autocratic alternative economic model.

These efforts build on the earlier discussions in Europe during Biden’s June trip, and it seeks to bring new elements of economic, regulatory, and technological cooperation into the Transatlantic relationship at a time when many democratic countries of the world are trying to come up with a better response and alternative to China’s assertive global economic engagement strategies. Beneath the surface of US-EU cooperation lurk deeper unresolved tensions on some core issues, including a dispute over steel tariffs and other trade competition concerns.

One interesting feature of the meeting in Pittsburgh, held there to show how a city that was formerly a manufacturing center in the industrial age has transformed itself into a new technological hub, is how little attention it received inside of America. The looming possible government shutdown narrowly averted this week, combined with an ongoing debate about legislation before Congress to make massive investments in the country’s infrastructure and social safety net and the deep political dysfunction producing a standoff that threatens a debt default by the US, crowded out the attention of most Americans this week. Those issues, plus the news that singer Britney Spears saw the yoke of her father’s legal oversight lifted by a court ruling, were all bigger news items in America this week than the US-EU trade and technology summit. America has a lot going on here on the home front, some of it important, some trivial.

But more broadly, the past two months have raised new questions about America’s strategic priorities and its core animating vision for its foreign policy and how it relates to close allies in Europe. Compounding these uncertainties are dynamics inside of Europe as well – continued strains from the pandemic and associated economic challenges and new concerns about energy security among key European countries. Furthermore, the departure of Angela Merkel after 16 years at the helm in Germany have produced more question marks from within Europe about what lies ahead. Finally, the implications of the strategic defeat suffered by the US and its NATO partners in Afghanistan – Afghanistan was the first major out-of-area NATO military operation – has not yet been fully discerned and contemplated on both sides of the Atlantic.

As Secretary of State Blinken travels to France this week, he carries with him new baggage that wasn’t with him on his trips earlier this spring and summer. Some of it relates to the operational and tactical mistakes the Biden team made on AUKUS and Afghanistan, showing a curious mix of narrow strategic group think and lack of sufficient tactical and operational coordination. If America can’t get those things right without alienating partners, how can it jointly take on the bigger challenges of China and climate change? Some of the new baggage is related to a chronic condition about America’s own political and economic system and whether it will produce some major breakthroughs in investing in America’s ability to compete in the world.

The Biden administration came into office seeking to hit the CTRL-ALT-DELETE button on Transatlantic relations, and some of its unforced errors, as well as changed circumstances in Europe, present them with a new set of challenges in the effort to get on the same page with its European partners. Mr Blinken’s trip to France and the little-noticed meeting in Pittsburgh last week are good first steps to resetting the Transatlantic reset

Brian Katulis is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, focussing on US national security strategy and counterterrorism policy