Semiconductors scarcity is one of the most visible effects of the pandemic-induced stress on supply chains and the increasing digitalisation. Due to its growing commercial and strategic importance, access to chips ranks high on the agendas of all major global powers, with the United States and China leading the race and the European Union gearing up to close the gap.

Brussels is in the process of penning the European Chips Act, a comprehensive strategy to boost in-house chip design and production that aims to double the EU’s sectorial market share by 2030. The draft should be ready by mid-2022 and help plan a common strategy. But the bloc must also make up for years of neglect and outsourcing to Asia.

Upwards of €200 billion are being invested in the digital transition through the Next Generation EU plan. Moreover, Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission announced it would relax antitrust rules to allow a degree of State subsidies. That’s a controversial instrument, but still one without which European industries simply cannot compete against heavily State-funded Asian and American companies.

That’s welcome news for big countries such as France, Germany and Italy, whose governments intend to support the industry’s growth by infusing cash and luring in major players. That’s the case with American chipmaking titan Intel, which is in advanced-stage talks with Berlin and Rome to expand its European chip manufacturing operation by building two major plants – and be granted hefty State aid.

The strategic importance of reshoring production is not lost on European capitals. According to a recent paper by Merics, an influential German think tank, the EU should strive for a “whole-ecosystem approach that considers all steps of the value chain.” This cannot be done solely by strengthening Europe’s ecosystem but requires strategic partnerships, write the authors, as the bloc must make up for its incomplete supply chain.

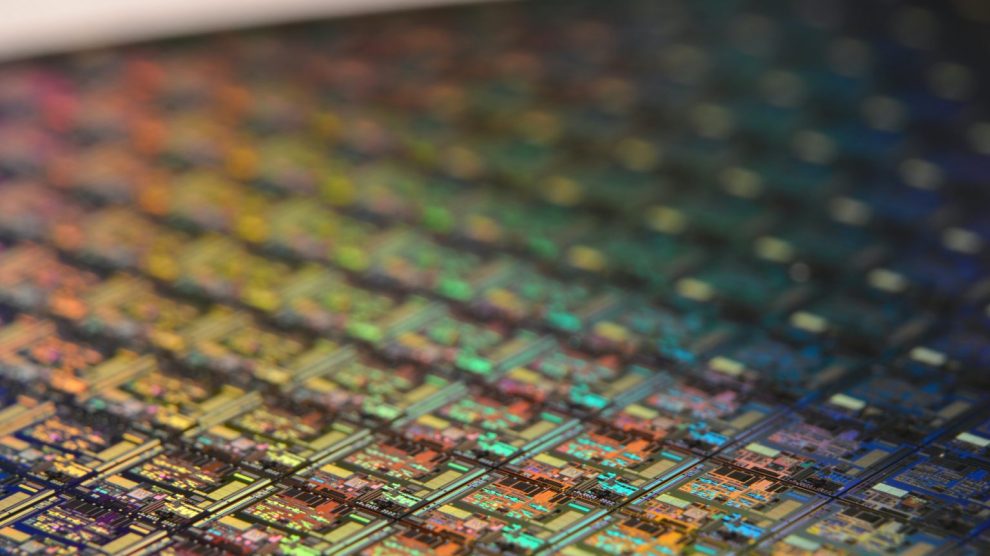

As things stand, the EU’s strong suit is research and development for technology innovation, whereas it’s lacking on the hardware side. Today Europe produces roughly 9% of the world’s chips and fares even worse when it comes to packaging – the final process in chipmaking, entailing cutting out single chips out of so-called “wafers” and readying them to be soldered into whatever device they end up in.

According to Steffen Kröhnert, an expert consultant, the most significant gap in Europe’s semiconductor capabilities is the ability to support advanced packaging – which according to Merics sits at 5% of the global total. Small companies might find workarounds, he told 3DInCities, “but that won’t work for cutting-edge and highly strategic tech such as 5G, high-performance computing, artificial intelligence and more.

Advanced packaging is also key to producing tomorrow’s most advanced chips. But outsourcing that production step also poses a major security issue, as the Merics report points out, because it “provide[s] a resource-efficient (skills, cost, time) attack vector to compromise a chip to implement a ‘kill switch’ or hardware backdoor.” A more resource-intensive feat compared to software exploits, but such a backdoor is persistent by design and significantly harder to detect.

“Government agencies and the military will unavoidably rely to some extent on commercial semiconductor manufacturing, and thus untrusted sources,” write the authors. Hence, it’s imperative to ensure the security and trustworthiness of chipmaking supply chains. And that’s where the Italian entente with Intel comes in, in the form of what would become the EU’s most advanced packaging plant.

Having more European advanced packaging capacity means that even if the “wafers” are produced elsewhere, there’s more leeway to send sensitive chips-to-be through a trusted European, American-operated facility and eliminate the possibility of a malevolent actor installing hardware backdoors at that key stage. That, and the added competitive advantage for the entire EU industry.