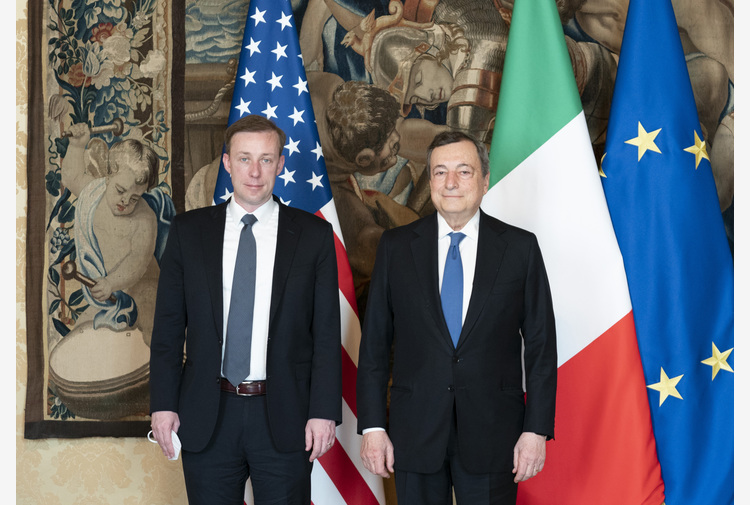

On Tuesday morning, the United States’ National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan was received in Rome by Prime Minister Mario Draghi and his diplomatic advisor, Ambassador Luigi Mattiolo, to discuss the situation in and around Ukraine.

The talks followed Mr Sullivan’s eight-hour long Roman meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi, on Monday. Both talks centred on the war in Ukraine or, to use Beijing’s diplomatic lexicon, which shows its irritation with Moscow, the “undesirable developments” of Russian moves.

The envoy of President Joe Biden sought to present Mr Yang with the US’ clear stance: Western allies know that China has shown evidence of willingness to support Russia in its invasion efforts, and they were prepared to take countermeasures should Beijing act to help Moscow, either militarily or economically, such as a way to avert sanctions.

On its part, China vigorously denied such claims. In an article that appeared later on the State-affiliated Global Times, Beijing sought to frame the American line as a disinformation operation. However, it also acknowledged that the two officials engaged in “candid, in-depth and constructive discussions” on bilateral relations.

The context

Previously, Washington sought to warn allies about the fact that China had signalled it was willing to provide military assistance to Russia in support of its invasion of Ukraine. The cables did not specify a timeframe or even if Beijing had already started to aid Russia.

On Sunday, Western newspapers reported that Russia had requested China’s military assistance at some time during the three-weeks long conflict. And while Beijing has publicly spoken in support of a peaceful resolution and diplomacy, Washington suspects it might be trying to covertly help Moscow.

Chinese and Russian diplomatic officials denied such claims. However, if that were the case, the implications would escalate the conflict on the geopolitical chessboard by some orders of magnitude. Assisting Russia, which has been sanctioned by much of the West, would elicit a Western response – and thereon the world would sail on uncharted waters.

Averting the decoupling

Washington is attempting to see through Beijing’s ambiguity towards the Russian war in Ukraine, which is officially neutral but evidently siding with Moscow – at least in its rhetoric and anti-West propaganda, which closely mirrors Russian disinformation narratives.

The Chinese leadership is grappling with an internal dilemma about the relationship it wishes to maintain with Russia. One way leads to to reinforce their “boundless” friendship, even in the face of conflict, carrying a high risk of a costly political and economic isolation and resulting in a democracy-versus-autocracy model clash. Another leads to Xi Jinping distancing himself from Vladimir Putin.

That’s the outcome the US is pursuing. In order for it to be effective, it needs a common and granitic front with its allies, not least to raise the stakes in a model clash that could cost Beijing dearly in terms of trade relations with the West.

This is where Rome comes into play, having returned, at least for a few days, at the centre of the international scene. That’s also due to PM Draghi’s Euro-Atlanticism, which marks a turning point compared to the previous governments led by Giuseppe Conte.

Meanwhile…

Mr Sullivan stressed it’s time for Western allies to stick together. The same was said on Monday by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman in a telephone conversation with her counterparts from France, Germany, Italy (Ambassador Ettore Sequi, Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and the United Kingdom. The five discussed “additional economic costs” to be imposed on Russia.

While Mr Sullivan was meeting Mr Mattiolo, the European Union published a new package of sanctions against Russia – its fourth – with several restrictions, including a ban on the export of luxury goods. This particular measure had allegedly been strongly resisted by the Italian government, although the latter denied it.

The diplomatic negotiations on the new measures have rekindled existing tensions between the EU’s hawks, led by Poland and the Baltic countries, and the alleged doves, whom the formers identify as Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria and accuse of prioritising their own economic interests.

Such divisions within the West are exactly what the US is seeking to avoid, so as to proceed swiftly with the measures against Russia and to show a united front against a possible axis of autocracies.

Mr Sullivan’s Roman mission, Vice-President Kamala Harris’s recent visit to Poland and Romania, and the latest rumours of President Biden’s upcoming trip to Europe seem to confirm this.

This phase may represent an opportunity for Italy to showcase its willingness to pursue a solution to the war and burnish its Euro-Atlanticist credentials in the wider geopolitical contest between the US and China.

Image: Filippo Attili/ANSA