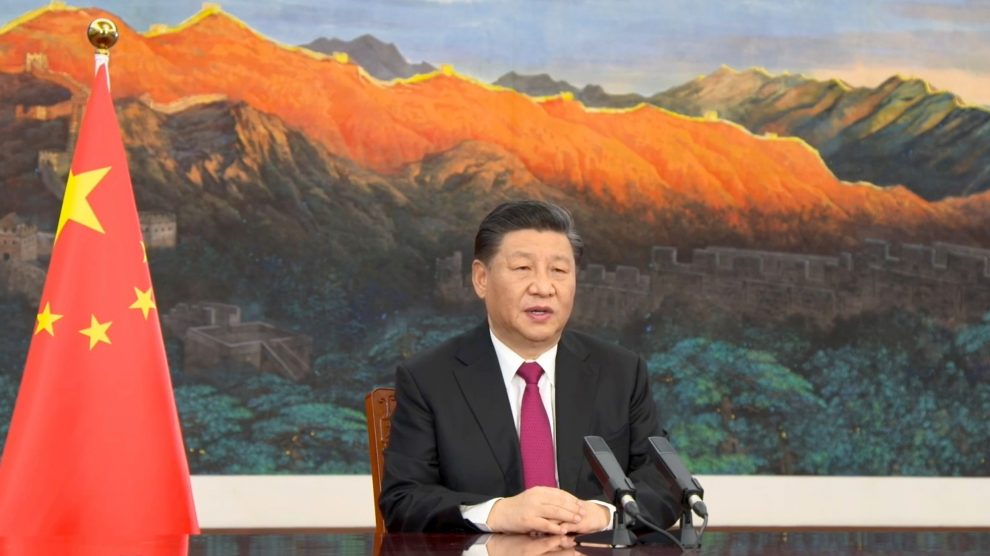

Chinese President Xi Jinping does not currently plan to attend in person the final G20 meeting in Rome, scheduled to start on October 30, wrote Bloomberg. Chinese officials reportedly cited Beijing’s Covid protocols, including possible quarantine mandates for returning travellers, as the overarching reason.

Bloomberg’s four sources added that this much was communicated at last month’s G20 meeting in Florence and that no news had been delivered ever since. While it is true that Mr Xi often announces his travel plans at the eleventh hour, he has not travelled outside China since January 2020.

More significantly, the leader’s repeated absences from crucial international summits stand in stark contrast with his purported commitment to multilateralism. Mr Xi did appear virtually at several events and held several bilateral calls in the past months, but his refusal to physically meet other world leaders is seen as a gravitas-stripping attribute – and an impediment to China’s diplomatic engagement.

As demonstrated during the recently held United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), summits with physical attendance provide an effective platform for bilateral or multilateral meetings on the side, which in turn spur greater coordination between partnering countries.

This comes at a crucial time for international relations, as globe-spanning issues – climate change, energy procurement, Covid vaccine supplies, supply chain troubles and shortages (especially with regards to semiconductors), as well as the Afghan crisis-in-the-making and the related G20 meeting – require globe-spanning measures.

Chiefly, China plays an outsized role in most of these dossiers. For instance, it accounts for 28% of climate-altering emissions (and plans to increase them at least until 2030), and yet Beijing failed to comply with the Paris Agreement it underwrote by not presenting updates to its nationally determined contributions (NDCs), the driving factors behind that global accord.

This instance exemplifies the struggle of a nation caught between upholding the concept of a multilaterally-driven world order (to contrast what Beijing perceives to be the hegemonic prowess of the West’s soft power) and actually engaging with other nations to pursue joint goals, which range from decarbonisation to vaccination and include major economic issues.

The refusal to engage might soon fan the flames of hostility towards China, especially as November’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow – which IPCC scientists described as the last chance to present impactful measures – nears. To put it in practical terms, Mr Xi knows other countries know that the Paris goals cannot be reached without China.

Given the Chinese president’s missed chance to travel to Rome (for both the Afghanistan and the final G20 summits) it becomes increasingly likely that he might just not show up in Glasgow, which in turn could highlight China’s partial disengagement on the climate issue and the dire consequences this entails.

Of course, it’s not as if China is detached from diplomacy. Yang Jiechi, a top Chinese diplomat, is scheduled to meet US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in Switzerland this week. This is the last in a series of high-level meetings that also included a phone call between Mr Xi and US President Joe Biden, who reportedly offered the former to meet in person – an offer he rejected.