In the race to ensure its future position in the semiconductors industry, the EU is at a juncture. As the Commission is penning the European Chips Act, and about to announce new rules for State aid, member States are splitting between those who push back against beefier State subsidies and those who are determined to shore up the industry by whichever means.

Europe’s dual engine – namely, France and Germany – is on the latter side, and so is Italy. Mario Draghi’s government, which is making strides towards bringing Italy on par with the EU’s leading countries, has made its position abundantly clear through the words and actions of the Minister of Economic Development, Giancarlo Giorgetti.

Dallying with semiconductors

A few weeks ago the latter met with French Minister of Economy Bruno Le Maire on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Rome. During the discussion, he highlighted the importance of “reflecting on the compatibility between technological sovereignty and State aids.” Both are keenly aware of the strategic importance of chips, which has been further highlighted by their scarcity in the past months.

It’s safe to assume that Mr Le Maire leant a receptive ear. Not only do Italy and France jointly own a chip making company, STM, but Emmanuel Macron’s France 2030 plan includes €6 billions for the semiconductor industry, and the country is slated to host the second iteration of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council series of meetings in spring.

Rome has a horse in this race, too. The government is reportedly leading the talks with a leading American chipmaker, Intel, to host an “advanced packaging” chip making facility in Italy, valued at approximately €4 billion or more and capable of creating one thousand new jobs. This would work in tandem with an even larger factory, which will likely be built in Dresden, Germany.

PM Draghi received Intel’s CEO Pat Gelsinger back in June and Mr Giorgetti discussed the dossier during his recent trip to the US. And according to Reuters, they aim to close the deal by year’s end. When commenting on these indiscretions, the minister all but confirmed them by stating that “there have been talks, there have been a series of meetings, [but] confidentiality helps in these cases.”

The European chip spat

Naturally, Intel’s choice to reinforce its European operations comes at a price – the investment monies the company is putting on the plate has to be met with an adequate response from the State that wishes to enter the race.

However, some fear that propping up the EU’s semiconductor industry – which is of crucial and ever-growing strategic importance across an increasing amount of industrial sectors – risks undermining the bloc’s competition rules. And this dilemma already caused a spat between two high-up European officials.

“We need to avoid a subsidy race that leaves everyone worse off,” cautioned the EU’s Danish antitrust chief and Executive Vice-President, Margrethe Vestager, during a speech in Leuven last Friday. “In the current circumstances, it becomes tempting for companies to try to play out governments against each other, scanning the landscape to see who would be willing to pay more. This risks letting taxpayers – whether European or American – pick up the bill, and get little from it.” She also added that supply chain interdependence must ultimately be accepted.

It only took a few hours for the bloc’s Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton, who also happens to be France’s top European official, to hit back with a thinly-veiled swipe at Ms Vestager’s approach during a speech in Dresden, the “Silicon Saxony” city where several semiconductors operation already exist and where Intel’s plant is likely to be built.

“Believing Europe should depend on others for chips is an illusion. Believing we could be satisfied with the partial control of this strategic supply chain is naive. Believing we should miss out on producing for the EU and also export to the rest of the world would be narrow-minded,” he said.

Reality check

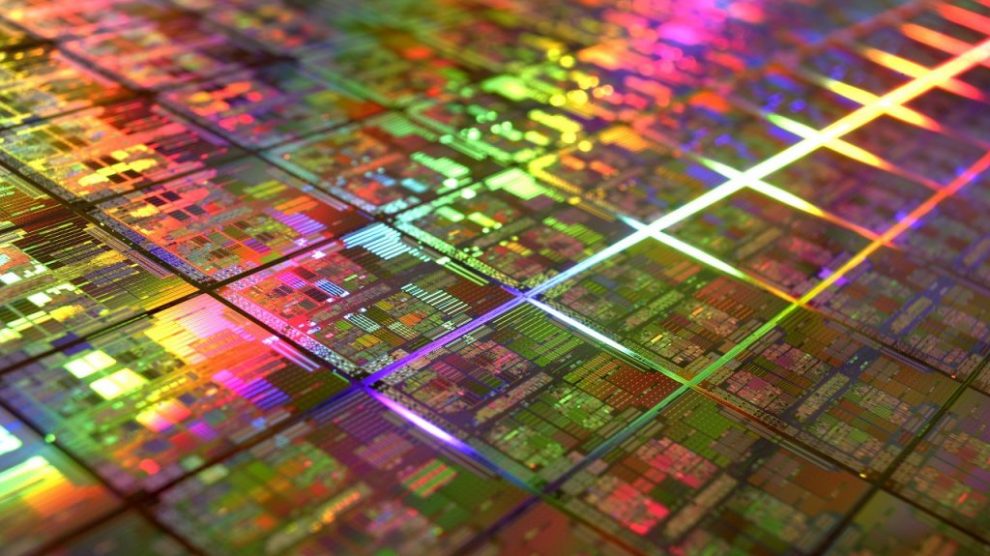

The EU did lose its chip-making prowess, descending to 8% (from 25% in 2000) of global market share. The dip is even worse when looking at leading-edge semiconductors: from 19% to zero. Much of it is due to European companies outsourcing chip production in Asia, whose highly innovative tech sector has blossomed and produced industry titans such as TSMC and Samsung.

As noted by a recent report by Kearney, a strategic consultancy company, Europe’s “limited local production capability and capacity” endanger its “technological sovereignty”, and thus it must “correct course to maintain long-term competitiveness.” The good news is that the bloc would benefit significantly from reshoring leading-edge chip manufacturing, according to the report, and “is well positioned to succeed.”

Going forward

To sum it up, Denmark and the Netherlands are leading the “frugal” charge (participated by Finland, Ireland, Romania and Sweden) to keep the Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen from watering down State aid rules to foster the growth of major industries. On the other side are France, Germany and Italy, standing by the line expressed by Mr Breton.

Meanwhile, Ms von der Leyen seems to express views sympathetic to the latters’ position as she toured the Dutch semiconductor company ASML on Monday, together with PM Mark Rutte along with Ms Vestager and Mr Breton. She stated that upwards of €200 billion from the NextGenerationEU plan will be invested in digital projects and stressed that the upcoming European Chips Act is geared at doubling the EU’s market share by 2030.

These objectives are decidedly out of reach without reaching for the States’ purse, especially as the US and Asian countries are heavily subsidising their own industries at the sound of billions. According to the analysts at Kearney, the EU must press on the pedal by incentivising leading-edge chip design and production and partnering with industry titans such as Intel. The path seems clear – and Italy seems determined to walk it.